Starting with un coup de foudre felt in a cemetery in Melbourne, Australia, I wanted to find out more about Milady. I began to travel across Europe, seeking an elusive fictional character hidden in a forgotten time. You can find the resulting historical fiction in serial form here: MILADY. And you might be interested in finding out about the background - here’s my first meeting with the young woman herself.

Following clues provided by Alexandre Dumas in The Three Musketeers, we know Milady was born an innocent, Anne de Breuil. She changed her name to Charlotte Backson when she fled to England and became a spy for France under the mentorship of the Comte de Rocheforte. We know she enjoyed court life both in France and England and that she changed her name again, probably by marriage, to Lady Clarik (Clarick) and then became known as Milady. We also know she died in 1628 by the sword.

My search began when Great Britain voted to leave Europe. My research revealed strange resonances between Anne’s time and our own. Poor Europe.

In short, Europe oscillated between the idea that she was intended to exist as an entity and a dread that any such consolidation would be brought about forcibly at the cost of each state’s independence and of each man’s personal right to order his daily life, his thoughts and his own affairs as he chose.

Victor-L. Tapié, 1967, France in the Age of Louis XIII and Richelieu, CUP

Milady, roughly the same age as Louis XIII, arrived in England at the beginning of the Thirty Years war in 1618. Neither Catholic France nor Protestant England wished to join a combined Europe which would make them pawns in the Holy Roman Empire, to be controlled by Philip IV and Spain.

Milady was brought up in a Catholic nunnery but learned Protestant hymns in England. There is much to learn about this young woman and the turbulent times in which she lived. How did she survive?

Let me show you where my ideas came from, how I went about researching, and where I found slivers of Jacobean history after a couple of World Wars.

The nature of history is reflective. What will happen next?

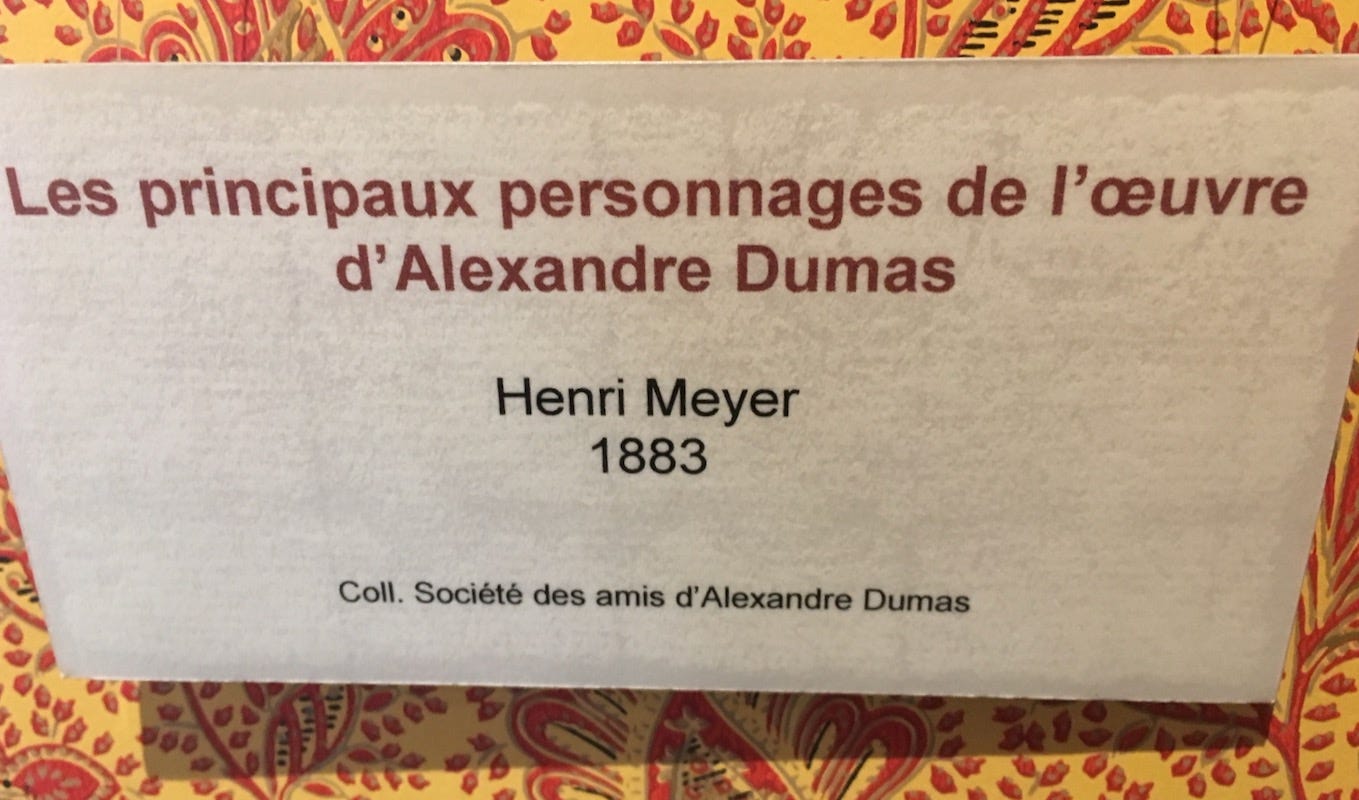

Let’s research (and search again) for signs of Dumas, Milady, and life in the seventeenth century.

What do you think? Did you ever feel sorry for Milady?

This was my first post - and it’s a film review!

Swashbuckling! Want some?

Kicking! Swords clashing! Running! Hitting! Flying backward dramatic falls! Beautiful horses! Sailing ships! Explosions! Women! Wait—Er … Soppy chaste romance? Blurrrrgggg …

Why subscribe?

Subscription is free to help Search for Milady and discover the archives.

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox.

Attributions

Please note all photos are mine excepting those attributed to other (more skilled) photographers.

Les Trois Mousquetaires by Alexandre Dumas (1844)

Dumas, A. (2008). The Three Musketeers.Tantor AudioBook Classics. (Original work published 1844). Read by John Lee

Dumas, A. (2006). The Three Musketeers.Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1844). Translation and Introduction copyright Richard Pevar, 2006

Dumas, A. (2016). The Complete D’Artagnan Novels. Bookhouse. (Original work published 1844). Translation: William Barrow (1817-1877)

To learn more about the tech platform that powers this publication, visit Substack.com.