“No,” said Athos; “don’t let us drink wine which comes from an unknown source.”'

Dumas

Back in August 2017, I found the book ‘Charlotte’ in Paris. Recommended by the bookshop assistant, it was about an artist, Charlotte Salomon, by David Foenkinos. In English, it answered my requirement to read a local epistle in situ, and I was drawn to it because of her name. If my son had been female, that child would have been called Charlotte, and, as habitual readers know, Milady, born Anne de Brueil, changed her name to Charlotte when she fled to England. And, as you know, when I searched for the seventeenth century I found layers of time, especially war, had wiped history away. Charlotte was a German Jew in the days of horror and she had been wiped away.

Although the account of Salomon’s extraordinary life was grim, it opened my mental floodgates to another aspect of character exposition - not Dumas’s creation whipped up from a blend of historic figures and story requirements - but rather how a personal search could intertwine with narrative. I found ’Charlotte’ almost as exciting as ‘Waiting for Godot’, a quest through space and time to find someone who once touched your heart, and who you would, probably, never meet.

So it was not the content of ‘Charlotte’ that intrigued me, but the form. The story, and life, of Charlotte Salomon was perfectly framed by the suicides of all her female relatives. Her death was a kind of bowing to the forces of injustice through not escaping when she might have. But, for me, the interest lay in the intrusion of the author, Foenkinos, his breathless admiration, and thrill when he came face to face with something she might have seen or touched, much like my Executioners Bread.

As far as imaginative constructs and flights of fancy go, I had not personally seen how much detail (or truth) lay in Charlotte’s enormous painted journal called ‘Life? Or Theatre?’ she created in the two years she lived rent free in an attic in the South of France supported by a wealthy American woman who recognised her genius.

Why do I feel so cynical about ‘genius’? Life? Or Theatre?

I remain glad Charlotte was able to express her trauma and grief and that she was recognised by her school. Only recently has her letter confessing to the murder of her father been published - revealing another facet to her person - before she, in her turn, was murdered by Nazis. And the dread that is racism and facism and oppression and the rise of personality and … here we are again.

In my case, the unjust treatment of Milady in The Three Musketeers so shocked me that I felt some public display was warranted. I could not find her biography already written, I could not see the play already staged. So, many years after the first shock, I realised the only person left standing to reveal her tale was me. And now, here I am, on this Substack, intertwining my search with her (fictional) life. Or theatre? With minimum poetry. And yet, you never know, I might sprinkle some jerked and patterned thoughts through the verbiage. Keep your eyes peeled.

While I slept in my French attic in 2017, a twenty-two year old started an event called ‘Shoot at Irma’ where Americans were going to fire their weapons at a hurricane. I still wonder if the bullets came hailing down on the shooters. Fifty-three thousand shooters had expressed an interest when I first heard of it. Lead rain. Civilisations do end.

My WorkAway, hosted by Marie, in Bay-sur-Aube continued. Marie’s friend Eric lived in a village called Chalancey. In the interests of research, we called in to see his demonstration of applying fresh mortar. He had already chipped out the old and showed Marie how to load up a trowel of new to apply between the ancient stones.

Eric proved to be an excellent tutor in the art of masonry. Perhaps it came from living in close proximity to such fine medieval stone buildings, such as his friendly neighbourhood Chateau (castle).

The Chateau was built over the source of a spring, enclosing the water for the nobles to use the water for personal use, their animals and their moat, and to mill their grain. I suppose in dry conditions the aristocracy kept hydrated while the poor dried to a crisp. The opposite of Pompeii’s the-people’s-taps-stay-on philosophy. Marie could not show me the Chateau, but the Lavoir is open for all to inspect and ponder.

A cool, still, silent reservoir, as big as a swimming pool, was locked within the walls of the Chateau. Once the castle had finished with it, water was allowed to flow into the public watering place, the Lavoir, for communal washing of people, clothes, and finally, watering the livestock. Marie pointed out the backbreaking effort involved in doing laundry by hand, noting how cold water and and the strong soap and effort destroyed women’s hands. The Lavoir was in use up to 1962 when running water came to individual homes.

The castle itself had a bridge over the road so nobles could avoid mingling with lower beings, I suppose. Or getting their feet wet.

On the way home Marie stopped to show me the Source of the River Aube. This was her most generous gift. I loved this place. It was as though time stood still. As though the world was holding its breath. As though the earth was giving birth.

It was a beautiful forested area where the waters bubbled calmly to the surface and learned to become the Seine.

"La Paix" by Paul Eluard

Published in 1942 during World War II

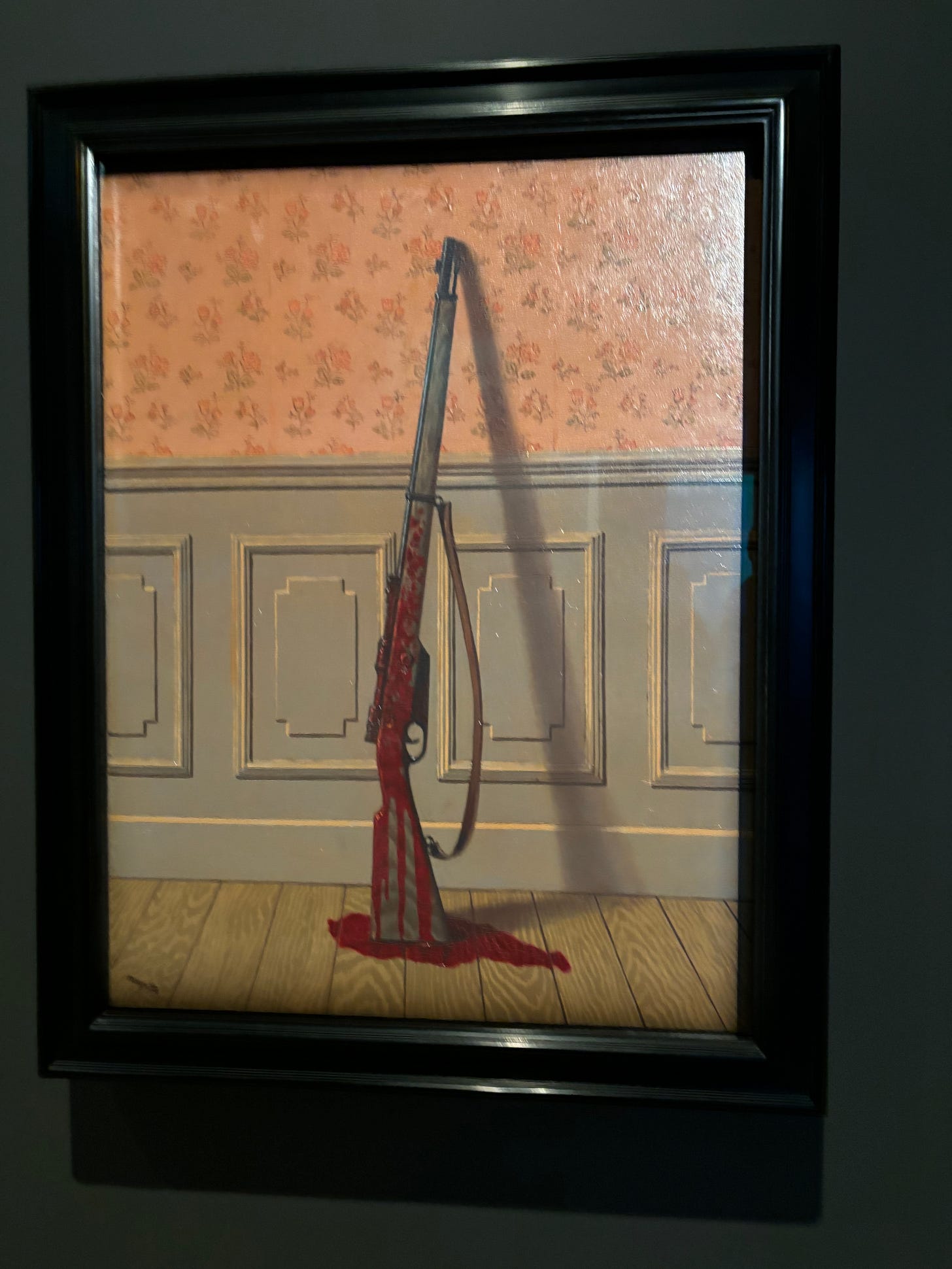

(Both Magritte and Eluard were surrealists. Perhaps the war made them so.)

The Paix

Sur la table, il y a une coupe de paix

Et une coupe de guerre.

Le pain de la paix nourrit les animaux doux.

Le sang de la guerre nourrit les animaux féroces.

Les armes sont lourdes.

Le pain est lourd.

La paix est légère avec des couleurs.

La guerre est légère avec du sang.

Quand la paix est là,

La guerre est cachée.

Quand la guerre est là,

La paix est cachée.

La guerre est plus forte que la paix.

La paix est plus forte que la guerre.

Translation:

On the table, there is a cup of peace

And a cup of war.

The bread of peace nourishes gentle animals.

The blood of war nourishes ferocious animals.

The weapons are heavy.

The bread is heavy.

Peace is light with colors.

War is light with blood.

When peace is here,

War is hidden.

When war is here,

Peace is hidden.

War is stronger than peace.

Peace is stronger than war.

fascinating and greatly enjoyed

Very pleasant!